Stratified survival analysis as a form of multitask/transfer learning

Introduction

In my previous post I discussed how gradient methods could be used to optimize the partial likelihood from the Cox-PH model. This post will use the notations and equations established there previously. In the machine learning context, the partial likelihood can be loosely thought of as a convex approximation of the concordance index score which measures the accuracy of assigned risk scores to pairwise comparisons between observations.[1] In this post I’ll outline the classical stratification procedure for the Cox model, how this can be thought of in terms of multitask learning as well as some possible extensions.

Imagine that a researcher is given two survival datasets that contain the same features but have a time measurement in different (and unknown) units. Since the partial likelihood is constructed using the relative event time orderings, these two datasets would not be able to be combined since we could not compare patient event times between them in a sensible way. Using a more realistic example, multiple survival datasets from different cancer patients may use different “events” of interest. For example, one dataset may use the actual death times of patients whereas others might use a surrogate endpoint indicative of the progression of the cancer. Once again in this situation comparing the event times between patients is problematic because they are on different scales (actual death versus an event known to happen some time before death).

The stratified partial likelihood is an elegant re-formulation of the partial likelihood that uses data-set specific event orderings (or risk sets).

\[\begin{align} &\text{Stratified log-partial likelihood} \nonumber \\ \ell(\bbeta) &= \sum_{k=1}^K \ell_k(\bbeta) \nonumber \\ \ell(\bbeta) &= \sum_{k=1}^K \Bigg\{ \sum_{i=1}^{N_k} \delta_{i,k} \Bigg[ \bx_{i,k}^T \bbeta - \log \Bigg(\sum_{j=1}^{N_k} y_{j,k}(t_{i,k}) \exp(\bx_{j,k}^T \bbeta) \Bigg) \Bigg] \Bigg\} \tag{1}\label{eq:stratacox} \end{align}\]The stratified log-likelihood shown in equation \eqref{eq:stratacox} is the sum over \(K\) datasets of each \(N_k\) summands. But because \(y_{j,k}(t_{i,k})\), the indicator as to whether patient \(j\) from dataset \(k\) was alive at time \(t_i\) in dataset \(k\), the relative rank orderings are all dataset specific. Also notice that there is a single \(p\)-dimensional \(\bbeta \in \mathbb{R}^p\) parameter vector that is shared by all the datasets. The final estimate of \(\hat \bbeta\) will therefore be determined by the direction of all \(K\) gradients. Specifically the gradient will be:

\[\begin{align*} &\text{Gradient of stratified likelihood} \\ \nabla_\bbeta \ell(\bbeta) &= \sum_{k=1}^K \bX^T_k(\bdelta_k - \bP_k \bdelta_k) \\ &\text{With elastic-net regularization} \\ \nabla_\bbeta \mp\ell(\bbeta) &= -\sum_{k=1}^K \bX^T_k(\bdelta_k - \bP_k \bdelta_k) + \lambda (\alpha \|\bbeta\|_1 + (1-\alpha)\|\bbeta\|_2^2) \end{align*}\]In the presence of regularization it is easy to see that if the effects of feature \(j\) differ between the datasets (i.e. they increase the hazard in some but decrease it in others), then coefficient will be rapidly shrunk to zero. A regularized stratified survival model therefore encourages coefficients weights only on features with consistent effects across the datasets.

Multitask learning

In the classical statistical learning framework we make the assumption that our observations are independently drawn from some distribution: \((y,\bx) \sim P(y,\bX)\), and we are trying to learn some some statistical regularities in the data in order to make predictions on new data. However our dataset may be made up of different samples, and the statistical relationship between the labels and the features will be similar but not exact between these different domains. In the case of the relationship between rental prices and the size of the apartment, in one city it may be that an extra square-foot of apartment space raises the price by \$1.50 whereas in another it could be \$2.75. The philosophy of multitask learning framework is that similar tasks (predicting prices in different cities) can be combined in an intelligent way by building some sort of shared representation to improve the learning process and ultimately generalization accuracy.

There is a tension however between capturing idiosyncratic representations specific to each dataset and those of a single shared representation. For example, if we were building a rental price predictor for the cities of Vancouver and Toronto we could either: (i) train two completely separate models, (ii) a single model using all the data, or (iii) two separate models whose optimization procedures are influenced by information from the other datasets. Case (iii) would be an instance of multitask learning. Notice that that stratified partial likelihood formulation is a form of multitask learning because all \(K\) datasets share one representation, a parameter \(\beta_j\), for the \(j^{th}\) feature. As an alternative approach, we could give each dataset its own set of \(p\) parameters and then use \(\ell_{2,1}\)-norm regularization to share information across datasets. For example using the least-squares regression case:

\[\begin{align*} &\text{Multitask learning with the \\(\ell_{2,1}\\)-norm} \\ \ell(\bB) &= \frac{1}{2} \sum_{k=1}^K \frac{1}{N_k} \|\by - \bX_k \bbeta_k \|_2^2 + \lambda \|\bB\|_{2,1} \\ \bB &= [\bbeta_1 \dots \bbeta_K] \\ \|\bB\|_{2,1} &= \sum_{j=1}^p \| \bB_{j\cdot} \|_2 = \sum_{j=1}^p \Bigg( \sum_{k=1}^K \beta_{j,k}^2 \Bigg)^{1/2} \end{align*}\]Since the \(j^{th}\) row of \(\bB\) represents the \(K\) different coefficient values for the \(j^{th}\) feature across all \(K\) datasets, the \(\ell_{2,1}\) norm is simply a sum of \(\ell_2\) norms across all the rows. Readers familiar with the group Lasso should note that this will encourage group-wise sparsity across the datasets: i.e. all coefficients are thresholded to zero, or are all non-zero. In other words, if the the \(j^{th}\) feature has a limited effect in many of the datasets, it will be forced to zero for all datasets. To see how this technically occurs, consider the (sub)gradient for the \(j^{th}\) feature in the \(k^{th}\) dataset.

\[\begin{align*} &\text{Multitask learning with the \\(\ell_{2,1}\\)-norm} \\ \partial_{\beta_{j,k}} \ell(\bB) &= -\bX^T_{j,k}(\by - \bX_k\bbeta_k) + \lambda \partial_{\beta_{j,k}} \Bigg(\sum_{q=1}^K \beta_{j,q} \Bigg)^{1/2} \end{align*}\]The subdifferential for any of the parameters from the \(k^{th}\) dataset contains only the response and design matrix data from that datasets, but, contains the parameter information across all datasets. This encourages only features will consistent effects across the datasets to be selected. If we assume that \(\beta_{j,k} \sim N(\beta_j,\sigma_j^2)\) then this will reduce the variance of the model estimates by averaging over several measurements. Alternatively, we could think of it as a technique which focuses our coefficient budget on only the most statistically reliable features.

Transfer learning

In real-world settings models are often built using training data which is drawn from a different distribution to the one we would like to make predictions on. For example we may be studying the genomic landscape of cancer patients that are from a single city and the same demographic background but would like to use its prognostic assessments for cancer patients anywhere in the world. Or we may wish to build a voice service engine that can be used by customers with English skills that vary in ability but only have labelled voice data from well-educated Stanford graduates. As a final example, we may have a new business platform with limited customer information, but have previous commercial data from previous enterprises of a similar nature. It would be useful to use that larger and but different dataset to inform the model that gets built using the smaller target dataset. All of these examples show the issue of transfering information from source dataset to a target distribution.

Transfer learning is conceptually similar to multitask learning but differs in that it is focused on building a model for a target domain, and data from a different source is only useful if it improves our predictive performance there. In applied examples, multitask learning tends to be for many datasets of a similar size, whereas transfer learning often happens when we have a large amount of data from a source distribution and little or no data from the target. As in the case of multitask learning, the more similar the two distributions are, the more we want to leverage shared representations.

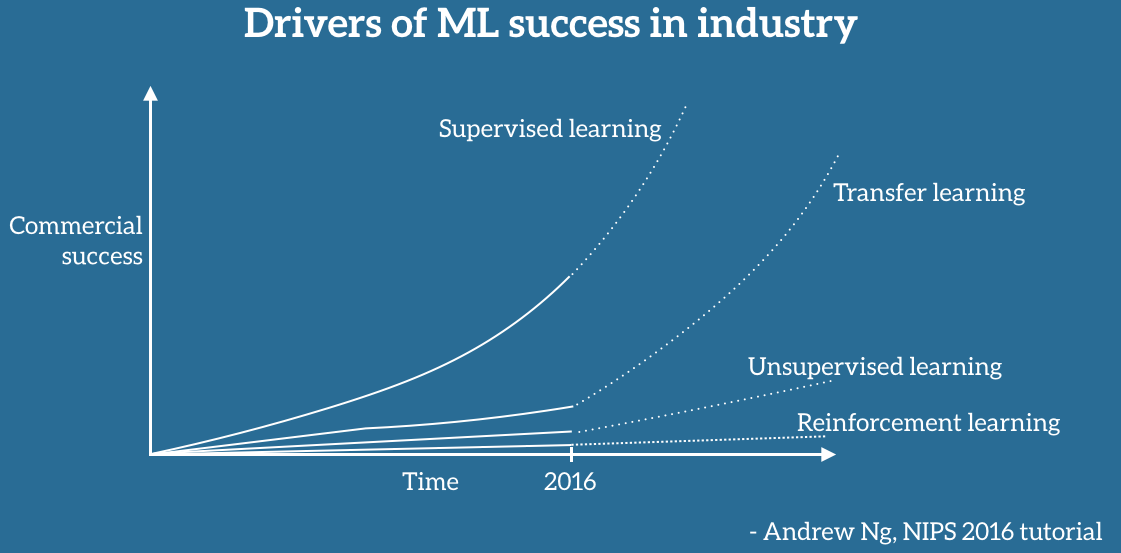

It is somewhat surprising that multitask and transfer learning are relatively small research areas (although rapidly growing) in academic machine learning because almost every real-world task would almost certainly benefit from it. I can think of very few datasets that do not share similarities with other datasets and presumably this information could be shared. This assessment of the value of the multitask/transfer learning is becoming well understood. At the 2016 NIPS conference Andrew Ng said that transfer learning will be the next driver of commercial success for ML. I would also recommend this review of transfer learning by Pan and Yang.

To give actual examples of how transfer learning would work, imagine we estimate a parametric model on a source dataset with many observations. If this model was a neural network, we could then use these hidden layer weights as initial starting values to train the network on the target dataset. If the target dataset is very small we could freeze the early layers of the network and just train the final ones. If instead the model was a simple linear regression, we could simply L2 norm difference between the parameters.

\[\begin{align*} &\text{Transfer learning with parameter weights} \\ \mp\ell(\bbeta_{T}) &= \frac{1}{2N_T} \|\by_T - \bX^T_T\bbeta_T \|_2^2 + \lambda \| \bbeta_T - \hat\bbeta_{S} \|_2^2 \end{align*}\]Figure: Andrew Ng's ML growth forecast

Combining transfer learning to the stratified likelihood

In the following transfer learning framework for the stratified survival model I outline an algorithm that has the following desirable properties: (i) some sort of shared representation (multitask), (ii) able to handle data-set specific features, and (iii) has adaptability between pure multitask and data-set specific modelling. For the first property, the stratified approach already shares a single covariate vector and this can be used as is. To handle features which may only appear in some datasets, we’ll need to encode “missing data” with zeros, but then adjust during our algorithmic procedures. Lastly, we can use relative weighting schemes between the different likelihoods to shift the balance between the source and target datasets.

To (re)establish the notation, suppose that we have \(k=1,\dots,K\) datasets each with an \(N_k \times p\) design matrix \(\bX_k\) and survival information \((\bt_k,\bdelta_k)\). Note that if a dataset does not contain the \(j^{th}\) feature, its is given a column of zeros in this location. Later we will show how to address this seeming problem. There is a single target dataset \(T \in {1,\dots,K}\) and the remaining datasets are the source \(S = \{1,\dots,K\} \setminus T\). To simplify notation we’ll assume that the target dataset is \(T=1\) and \(S=\{2,\dots,K\}\).

\[\begin{align} &\text{Transfer framework for stratified partial likelihood } \nonumber \\ \ell (\bbeta) &= \frac{1}{N}\Bigg(\pi_T(\tau) \ell_1(\bbeta) + \sum_{k=2}^K (1-\tau)\pi_k \ell_k(\bbeta) \Bigg) \tag{2}\label{eq:trans_strat} \\ \pi_k &= \frac{N_k}{N}, \hspace{3mm} \sum_k N_k = N \nonumber \\ \pi_T(\tau) &= 1-(1-\tau)\pi_S, \hspace{3mm} \pi_S = \sum_{k\neq T} \pi_k \nonumber \end{align}\]The transfer-stratified likelihood approach seen in equation \eqref{eq:trans_strat} is still the sum over the \(K\) different datasets with the only (current) difference that we add a hyperparameter \(\tau\) which captures the degree of transfer. When \(\tau=0\), the model becomes the stratified approach where each dataset is weighted by its number of relative observations. If \(\tau=1\) then the dataset reverts to a Cox model estimated on only the target dataset. When \(\tau \in (0,1)\) then the target dataset will receive a weight above is “fair share” \(N_T/N\). The more similar the data generating process is between the source and the target distributions, the more it makes sense to set \(\tau\) close to zero, although in practice the parameter \(\tau\) should be determined by cross-validation. What is cool about this transfer learning approach is that it is very close to a free lunch. If the source datasets are useless, \(\tau\) will be revealed to be close to zero, and if there is shareable information it can be optimized to some non-zero value. Of course hyperparameter selection is inherently noisy, but the downsides are very small.

For the inclusion of an elastic net penalty term we will need to add a term to adjust for the fact that some columns of \(\bX\) will be zero for some of the datasets (since we encoded zeros into variables that were not found in some datasets). As that the gradient of the likelihood for the \(j^{th}\) covariate in the \(k^{th}\) dataset is \(\bX_{j,k}^T(\bdelta_k - \bP_k \bdelta_k)\), than if \(\bX_{j,k}^T\) is a vector of zeros, there will be no contribution to the overall gradient in the \(j^{th}\) direction from that dataset. But in the presence of regularization the magnitude of the gradients matters for the relative amount of shrinkage, so we need to ensure that variables are not shrunk simply because they are only found in a fraction of the datasets.

\[\begin{align} &\text{} \nonumber \\ \mp\ell (\bbeta) &= -\frac{1}{N}\Bigg(\pi_T(\tau) \ell_1(\bbeta) + \sum_{k=2}^K (1-\tau)\pi_k \ell_k(\bbeta) \Bigg) + \frac{1}{2} (1-\alpha)\lambda \|\Gamma \bbeta \|_2^2 + \alpha \lambda \|\Gamma^2\bbeta \|_1 \tag{3}\label{eq:trans_enet} \\ \Gamma^2 &= \text{diag}\Bigg(\sum_{d \in D_1} \pi_d, \dots, \sum_{d \in D_1} \pi_d \Bigg), \hspace{3mm} D_j = \{k: \bX_{j,k} \neq \boldsymbol{0} \} \nonumber \end{align}\]By including the diagonal matrix \(\Gamma\) in equation \eqref{eq:trans_enet} we ensure that the regularization terms are shrunk by an amount proportional to the “missingness” of the variable across datasets. It is useful to see the (sub)gradient of our model to see how we will perform the gradient updates.

\[\begin{align*} \frac{\partial \mp\ell(\bbeta)}{\partial \beta_j} &= -\frac{1}{N}\Bigg( \sum_{q \in D_j} \pi_q \Bigg)^{-1} \Bigg(\pi_T(\tau) \frac{\ell_1(\bbeta)}{\partial \beta_j} + \sum_{k=2}^K (1-\tau)\pi_k \frac{\ell_k(\bbeta)}{\partial \beta_j} \Bigg) + (1-\alpha)\lambda \bbeta + \alpha \lambda \partial_{\beta_j} \|\bbeta \|_1 \\ &= -\frac{1}{N}\Bigg( \sum_{q \in D_j} \pi_q \Bigg)^{-1} \Bigg(\pi_T(\tau) \bX_{j,1}^T(\bdelta_1 - \bP_1 \bdelta_1) + \sum_{k=2}^K (1-\tau)\pi_k \bX_{j,k}^T(\bdelta_k - \bP_k \bdelta_k) \Bigg) + (1-\alpha)\lambda \bbeta + \alpha \lambda \partial_{\beta_j} \|\bbeta \|_1 \end{align*}\]The gradient for this stratified-transfer model is identical to the regularized stratified partial likelihood with two exceptions: it allows for a non-proportional weighting scheme by setting \(\tau \neq 0\) and it includes a “missing variable” offset term. However because the loss function is convex (because a non-negative weighted sum of convex functions is convex), proximal gradient descent methods can be used to be an efficient method to finding the \(\arg \min\).

Conclusion

This post has shown the relationship between stratified survival modelling and multitask learning and how it can be extended to the transfer learning case. Experiments based on propriety datasets suggest this approach can improve single-dataset models in the genomics context for survival modelling. The fact that the stratified model uses a single coefficient vector may be too restrictive and the inclusion of dataset specific parameters could be a useful addition.

-

However in the statistical framework, the partial likelihood function is used because it approximately proportional to a more complex likelihood and is easier to optimize when performing parameter inference. ↩